Bruntingthorpe is where the motor industry parks hundreds of cars that are waiting for customers, where car and bike manufacturers go to test new models and where one biker got off a speeding charge using the novel strategy of proving his bike couldn’t go that fast. And in 2009, unexpectedly, it was the location for the last flight of the Victor.

It was also where, for more than 30 years, scribblers and photographers would go to test cars and take pictures for the pages of car and bike magazines and, later, websites. But now Cox Automotive, which took over Bruntingthorpe owners C Walton Ltd in April, is closing the track’s gates to everyone but major motor industry clients.

My introduction to car photoshoots was to spend six hours on a very wet day at Brunters – as everybody called it – holding an umbrella over a photographer’s camera. Not even over the photographer, you note, but over his vast medium-format Mamiya which was pointed at a couple of modified Ford Escort vans. The result was the Fast Car cover seen here.

My introduction to car photoshoots was to spend six hours on a very wet day at Brunters – as everybody called it – holding an umbrella over a photographer’s camera. Not even over the photographer, you note, but over his vast medium-format Mamiya which was pointed at a couple of modified Ford Escort vans. The result was the Fast Car cover seen here.

I was actually more interested in the glimpses through the doors of the hangar that acted as the backdrop for that cover shot. Inside it was XH588, the Avro Vulcan that would later be returned to flight.

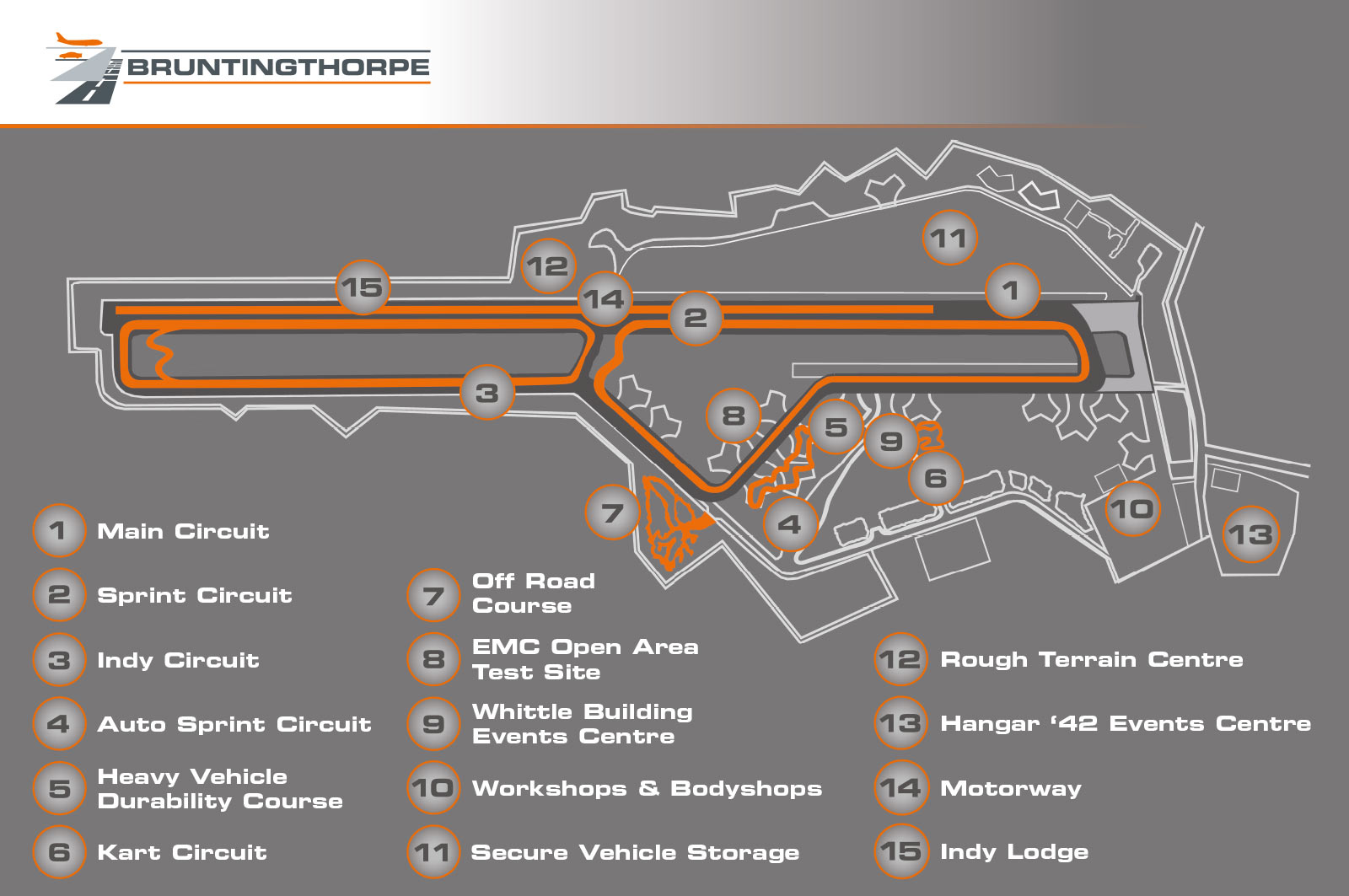

The hangars were a handy backdrop for pictures, but the real work took place out on the track. Bruntingthorpe was a Second World War bomber base that became a private airfield and then a test track. It offered a full circuit more than four miles long, almost half of that a broad, 10,000ft runway, one of the longest in the UK. It was uphill for the first third and downhill for the rest. The gradients and the track surface – ancient concrete, always covered in ‘marbles’ – made it less than ideal for acceleration testing, and was famous for leaving cars with chips in the windscreen and road rash around the wheel arches.

Bruntingthorpe, I quickly learned, was like no other place on earth. The Brunters greasy spoon café was legendary among car hacks (though rivalled by the Old School Café near Chobham and, for those really in the know, the Little Chef near Millbrook). The airfield had a unique microclimate where it was possible to be freezing cold all day yet come home with sunburn.

When you arrived the cheery Brummy security guard would hand you a walkie talkie, which was occasionally used to ask us to vacate the track for a few minutes while aircraft landed, as Bruntingthorpe was still an operational airfield. One such call came when we were sharing the track with a full-size articulated lorry, which was pounding around for lap after lap testing tyres. We dutifully stopped what we were doing and parked up at the end of the main runway, then heard the familiar rumble of the truck approaching.

It swept around the 180-degree turn that leads onto the runway and headed off down the straight in a tornado of dust. It had just gone out of view over the crest when a Cessna appeared about 50ft over our heads, sinking gently down towards the concrete.

It, too, disappeared over the crest and we waited for the bang and fireball as the plane caught up the truck, but there was nothing. A couple of minutes later the truck appeared, and instead of rushing past as it had done all day it pulled up, the brakes grinding and hissing as it juddered to a halt next to us. The driver exploded out of the cab, gesticulated down the runway and shouted DID YOU SEE THAT F***ING PLANE!

His radio wasn’t working...

A lot of what I did there involved performance testing modified cars. The mag’s insurers went through several phases about how this was to be handled: at one stage we had to drive the cars, then there was a stage where the owners had to drive but we had to be present. Some drove frustratingly slowly, perhaps due to the unfamiliar surroundings of an airfield or maybe because they never drove their (often expensively tuned) cars at anything like their potential. Acceleration tests are a combination of finesse and brutality, and I remember testing one car with the owner in the passenger seat and after the first run asking if he was happy or wanted me try again. A very small voice from the passenger seat said ‘no, no… that’s fine.’ Others owners were thrown by the lack of visual cues to speed on the wide runway and had to be told very firmly that now was a good time to brake – as the end of the concrete hurtled towards us.

There was an almighty bang and a shudder through the whole car. I was convinced the timing gear had come adrift, and that the silvered paper strip with the acceleration times printed on it would soon be accompanied by my P45

GPS and the V box were still in the future, and the timing equipment I was using consisted of a sensor which bolted on to a road wheel, feeding data by cable to a control box in the cabin. It had to be calibrated for the car’s tyre size, for which there was a measured mile marked out on the runway: if you missed the mark you had to go all the way around the lap and start again, so you quickly learned not to miss it.

The wheel sensor was retained by a series of clamps, each of which slipped over one of the wheel nuts and gripped it as its fixing nut was tightened. In theory, at least. It never felt very secure so there was always concern that the thing might fly off during performance testing.

The first time I had to fit it was on a modified Escort Cosworth. We did one run, recording 0-60mph in a fraction over five seconds, and a top speed around 150mph. Then on the back straight, on our way back to the start of the runway for a second run, there was an almighty bang and a shudder through the whole car. I was convinced the timing gear had come adrift, and that the silvered paper strip with the acceleration times printed on it would soon be accompanied by my P45. I gingerly wound down the passenger window to assess the damage – but no, the sensor was still spinning around on the front wheel.

It turned out that a rear tyre had thrown a tread, which had exited through the glassfibre sill extension, making a hole the size of a dinner plate. Half a minute earlier we’d been braking from 140mph as the end of the runway loomed…

Inevitably the cock-ups are the events that tend stick in the mind, but there were plenty of good moments too. Maxing out my BMW M535i on the wrong side of 140mph, for one, nailing an epic nine-car tracking shot for the lead image of a feature another. The fun – work, I mean, it was all hard work – comes to an end in August. Bruntingthorpe may already be ‘the industry’s best-kept secret’. Excluding media from the facility will certainly keep it that way, and that's a shame for the auto magazine folk who have used it so successfully for such a long time, and for their readers.